One of the finest fast bowlers of the post-war era

John Snow is regarded as one of England’s finest fast bowlers of the post war period, being England’s finest bowler between the eras of Truman and Willis. He could be an ‘enfant terrible’ at times and the despair of some captains. On his day he was as hostile as any fast bowler and a match winner.

He was recommended to the county as a batsman by the Sussex coach Ken Suttle who said of John that he was a “magnificent hitter of the ball”, but his bowling was “erratic and not very hopeful”.Snow was born in Worcestershire on 13 October, 1941, the son of a vicar and came to Sussex when his father took over a parish in Bognor Regis. He attended Christ’s’ Hospital, near Horsham before he moved to Chichester High School for Boys.

He played for Sussex Young Amateurs and the Junior Martletts before joining Sussex as a batsman in 1961. In his second match he scored 15 and 35, although his bowling talent had already been recognised. In his early years for Sussex Snow continued his training for the teaching profession, teaching at Woodingdean Primary School in Brighton.

His cup debut was the final

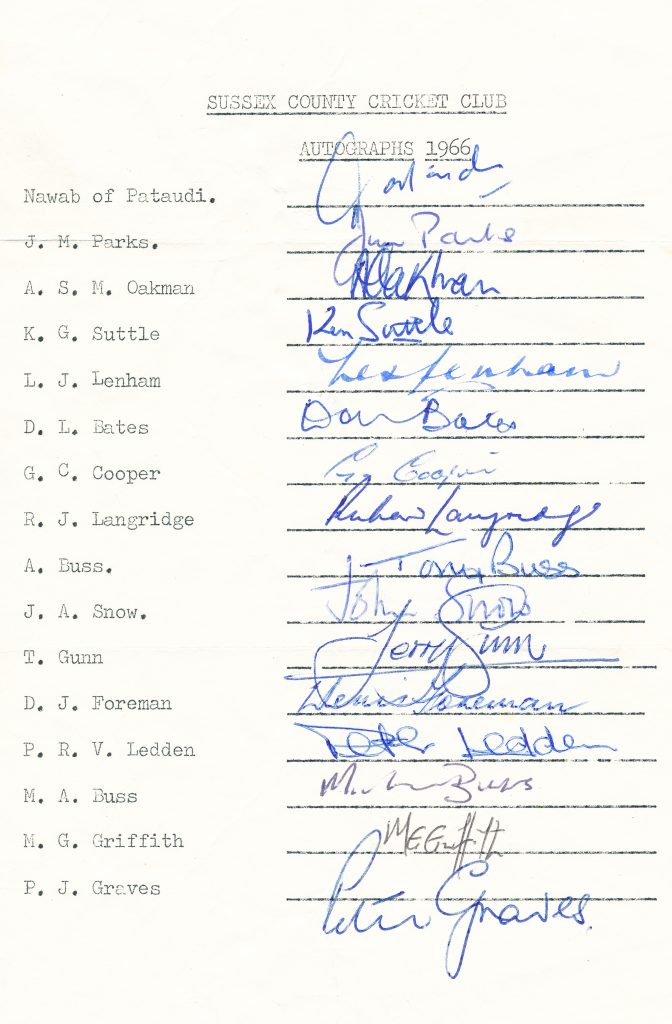

In 1963 Snow played twelve first class matches for Sussex but was good enough to be included in the team to compete for the very first Gillette Cup Final at Lord’s and in his eight overs took 3 for 13 in his side’s win against Worcestershire. He continued this success the following year when Sussex defended the title. With 77 wickets in 1964 and 100 in 1965, Snow had done enough to impress the selectors and he was called up for the two Test matches against New Zealand and South Africa. In 1966 he took 114 wickets for Sussex and topped the averages for the second season. He was now a regular in the England team. He was now focused on his bowling but he still had the occasional good batting performance as when he made 50 for the county and then in the final Test against the West Indies partnered Ken Higgs in a partnership of 128 in which he scored 59.

Snow had done enough to impress the selectors and he was called up for the two Test against New Zealand and South Africa. In 1966 he took 114 wickets for Sussex and topped the averages for the second season. He was now a regular in the England team. He was now focused on his bowling but he still had the occasional good batting performance as when he made 50 for the county and then in the final Test against the West Indies partnered Ken Higgs in a partnership of 128 in which he scored 59.

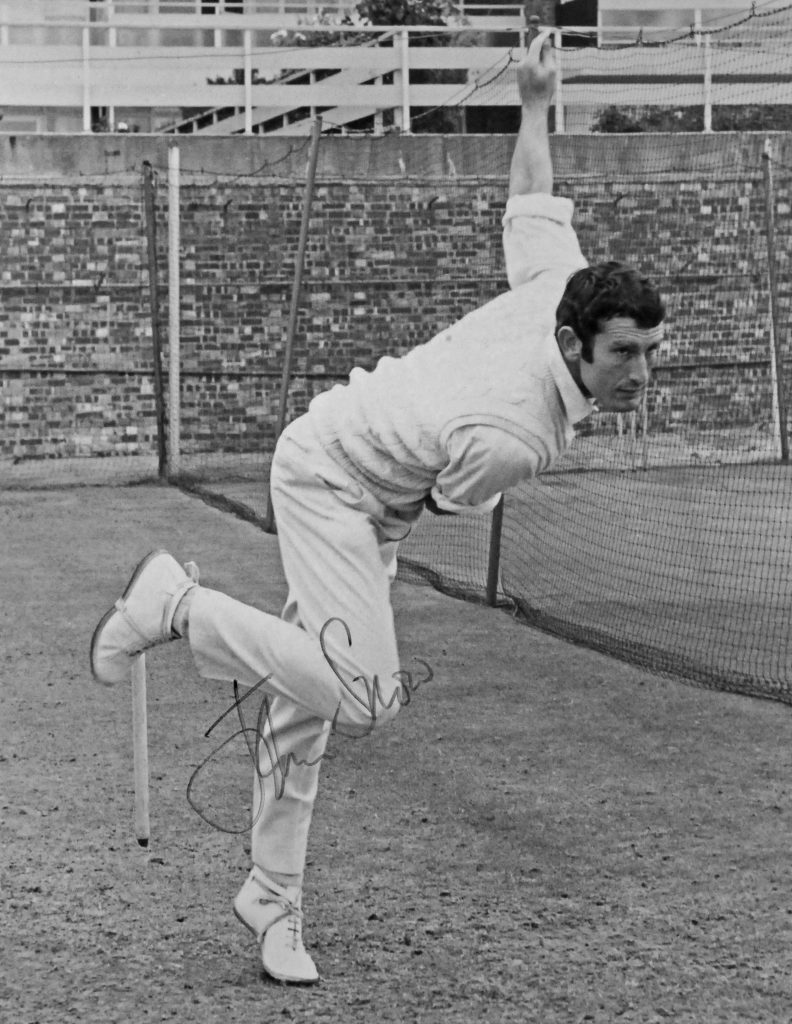

A languid, almost lazy run-up was deceptive

Playing more for England meant that he had fewer games for Sussex. He did not reach 100 wickets again for Sussex but in the games he had, he gave away few runs for the wickets he got, often having an average of less than 20 in games.

In his first couple of years for England it was as medium pace seam bowler although with his languid, almost lazy run-up, his speed was deceptive. Over the winter of 1965/66 he went to South Africa, not having been chosen for the tour to Australia, and changed his bowling action so that when he returned for the summer of 1966, he had a more classical style which enabled him to have more control and cut the ball sharply off the pitch. He saved his most aggressive, hostile bowling for Test matches as when playing against the West Indies in the winter of 1967/68 he took 27 wickets in the four Tests including 7 for 49 at Sabina Park. The following summer he took a further 17 Australian wickets. By this time Snow was able to vary his pace and include in his armoury the short pitched ball which lifted quite suddenly.

Regaining the Ashes in 1971

In the winter tour of 1970/71 against Australia the presence of Snow was one of the main reasons why Illingworth’s team regained the Ashes. His 7 for 40 in the Third Test saw Australia crumble to 116 in their second innings, and England win by 299 runs. He was dropped a few times in the 1970s but usually recalled when the going got tough as when he took 24 wickets against the 1972 Australians, and 15 wickets in three Test against the West Indies in 1976. Of his 202 Test wickets, 83 were against Australia and 72 against the West Indians. In all Snow played 49 Test for England and was wicketless in just one of these matches.

Dropped

John Snow, like others before him, suffered at the hands of a committee that was too quick to drop him. In the 1971 season after John had taken only three wickets for 232 runs in three matches, the committee decided to take action. In his instance the way he used to lounge around the outfield when not bowling was not appreciated. His bowling performances, and more especially his fielding, have been so lacking in effort that the selection committee had no alternative. He accepted the criticism but pointed out that his games for England took their toll. He took a month off the game and in his return game took 11 wickets in the win against Essex, leading to another recall by England, to play against India. This was the occasion for the by now infamous incident involving Sunil Gavaskar. Snow had rescued England in the First innings making his highest score of 73. With India needing 183 to win in their second innings, Snow took the wicket of the opener Ashok Mankad leaving India 21 for 2. Gavaskar then went for a quick single and as Snow went for the ball, he knocked Gavaskar over. They both got up uninjured but with the incident looking far worse than it actually was, the press had a field day.

John left Sussex in 1977 and went on to publish two volumes of poetry, and after playing some Sunday League games for Warwickshire in 1980 retired to found his own travel business specialising in cricket tours. He did though return to the cricket club as a member of the Sussex committee before becoming vice-chairman.

The Nawab of Pataudi on John Snow

Of Jon Snow, the Nawab of Pataudi, captain of Sussex in 1966 said, Ideally a bowler of John Snow’s tremendous pace should be used in short spells with adequate rest in between and he is usually more impressive and effective as a result. I knew this as well as he did but much as I wanted to help him, I had to be tough with John. Often I was forced to keep him on for lengthy spells because this was necessary for the team’s success.